Customer journey mapping is one of those practices that nearly everyone agrees is valuable but few organizations do well. The workshops feel productive, the visualizations look impressive, and the insights seem real. But six months later, most maps sit untouched in shared drives while decisions get made the same way they always were.

The problem isn't the mapping itself. It's that teams treat the map as the goal rather than a means to an end. What you're really after is shared understanding, visible pain points, and a basis for prioritization. The map is just the vehicle.

What is customer journey mapping?

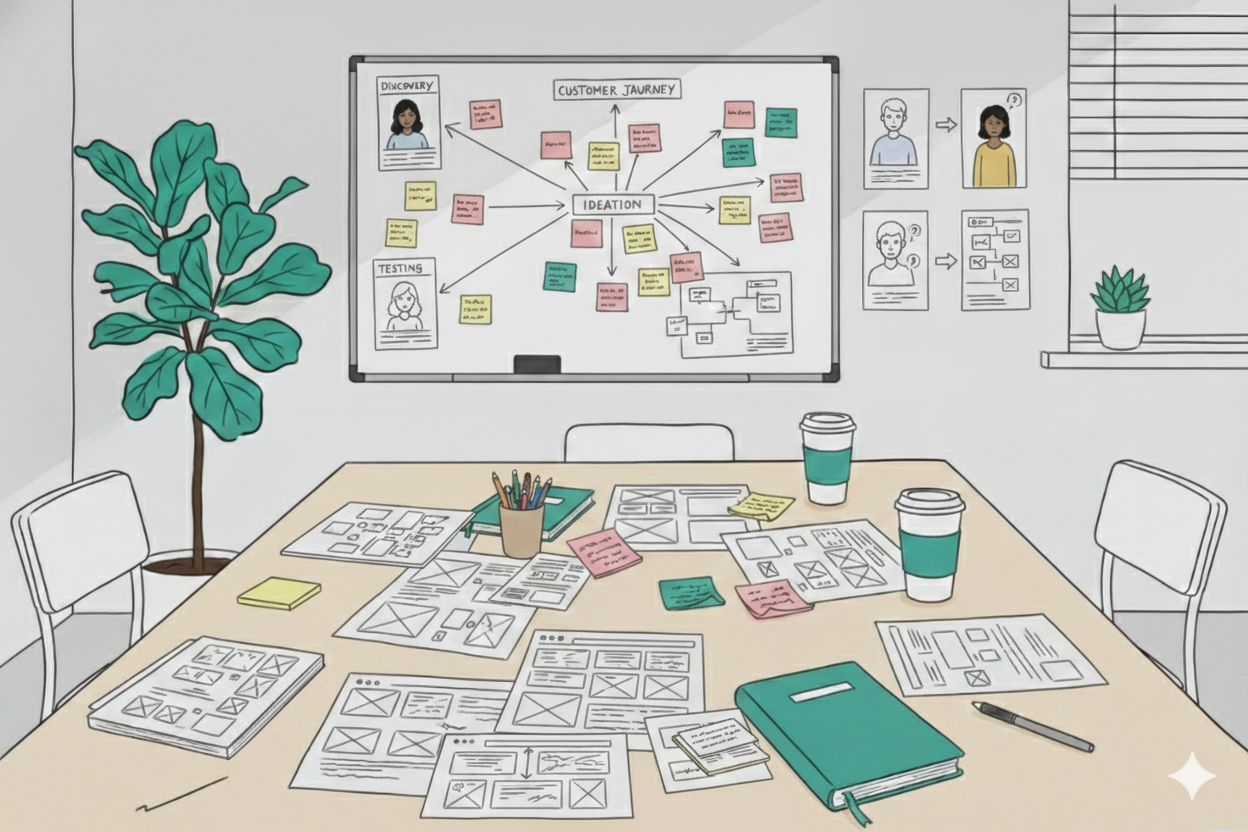

Customer journey mapping is the process of visualizing the end-to-end experience a customer has with your organization. It captures the stages they move through, the actions they take, the touchpoints they encounter, and how they feel along the way.

A journey map serves two purposes. First, it's an artifact that makes the customer experience tangible and shareable. Second, and more importantly, it's an alignment tool. When product, support, marketing, and operations look at the same map, gaps become visible, disagreements surface early, and priorities get clearer.

One distinction worth making: journey mapping is the activity of creating and maintaining maps, while journey management is the broader practice of using those maps to inform decisions, governance, and improvement over time. Mapping is an input. Management is the operating model.

Why most journey maps fail

Before getting into how to build a map, it's worth being direct about why most maps fail. They get created, presented once, and forgotten. This isn't a skills problem or a tools problem. It's a design problem.

Journey maps fail for three reasons.

They're built as deliverables, not decision tools. The goal becomes "finish the map" rather than "change how we work." Teams optimize for visual polish and comprehensiveness instead of utility, and the result is a beautiful artifact no one knows how to act on.

No one owns them. After the workshop ends, the map has no clear owner. No one keeps it current, no one champions its use in planning conversations, and no one notices when it goes stale.

They're disconnected from how work gets prioritized. The map lives in one place while the roadmap lives in another. Pain points get documented but never make it into the backlog. The map exists in a parallel universe from the decisions it was supposed to inform.

The fix isn't better facilitation or fancier tools. It's designing for what happens after the workshop ends.

What to include in a customer journey map

Journey maps can include many elements, but more isn't better. The components you include should serve your purpose.

Stages

Stages are the high-level phases of the customer experience: awareness, consideration, purchase, onboarding, usage, renewal. They provide the horizontal structure of your map.

Keep stages broad enough to remain stable over time but specific enough to be meaningful. Most journey maps work well with five to eight stages. More than ten usually means you're mixing stages with steps.

Steps

Steps are the specific actions customers take within each stage. They're more granular than stages and represent where friction actually happens.

A customer might move through "consideration" smoothly overall but hit a wall at the specific step of comparing pricing options. Steps make that visible. Map what customers actually do, not what you want them to do, which requires evidence rather than imagination.

Touchpoints and channels

Touchpoints are moments where customers interact with your organization. Channels are the mediums through which those interactions happen: website, app, email, phone, chat, physical locations.

Map both digital and human touchpoints, and pay particular attention to channel handoffs. When someone moves from self-service to talking to a human, or from mobile browsing to desktop checkout, experience often breaks down. Don't forget touchpoints you don't control either. Customers read reviews, ask friends, and post on social media, and these shape the journey even if they're not your channels.

Emotions and pain points

Emotions capture how customers feel at each step: confident, confused, frustrated, relieved. The emotional layer transforms a process diagram into an experience map.

Pain points are the friction moments that matter most. They're where expectations and reality diverge, where customers get stuck, where they consider abandoning the journey. Don't just list emotions. Connect them to causes. "Customer feels frustrated at checkout" isn't actionable. "Customer feels frustrated because shipping costs appear only at the final step" is something you can fix.

Backstage processes

Backstage processes are internal actions that support or undermine the customer experience: the systems processing orders, the teams handling requests, the handoffs between departments.

Including backstage processes helps identify where operational breakdowns cause customer pain and builds empathy across functions. When support sees how an upstream process creates the complaints they handle, conversations change. If you go deep on backstage, you're moving toward service blueprinting, a more detailed format that connects customer actions to front-stage interactions, backstage processes, and supporting systems.

Types of customer journey maps

Not all journey maps serve the same purpose. Match the format to the need.

Current-state maps document the experience as it exists today. They're the most common starting point and the foundation for improvement efforts.

Future-state maps visualize the experience you want to create. They're useful for aligning on a vision and guiding design decisions, but only valuable when grounded in current-state understanding.

Day-in-the-life maps zoom out to show the customer's broader context, not just their interactions with you. This reveals opportunities you'd miss by focusing only on direct touchpoints.

Service blueprints add operational depth by connecting customer actions to front-stage and backstage processes. They're more complex but invaluable for identifying internal breakdowns.

Don't try to do everything in one map. A map attempting to show current state, future state, backstage, and day-in-the-life context becomes too complex to use. Start with current-state for most teams.

How to create a customer journey map

Here's a practical process for building a journey map. This assumes you're creating a current-state map for a single persona.

1. Define your scope

Pick one persona and one journey. This is where teams most often go wrong. The temptation is to map everything: all customer types, all journeys, all touchpoints. Resist it.

Decide where the journey starts and ends. "Customer journey" can mean awareness to purchase, onboarding to first value, or the entire lifecycle. Be explicit about your boundaries. Clarify your purpose as well. Are you trying to align stakeholders? Identify improvement opportunities? Inform service design? The purpose shapes what you include.

2. Gather customer evidence

This step separates useful maps from fiction. You need evidence of what customers actually experience, not assumptions about what they should experience.

Start with existing research: interviews, survey responses, support tickets, analytics, usability studies. Most organizations have more customer evidence than they realize. The problem is usually synthesis, not collection. Mix qualitative and quantitative data. Qualitative research tells you why customers feel and behave the way they do, while quantitative data tells you how many share those experiences.

If you don't have enough evidence, you can start with an assumption-based map built on internal knowledge. Just don't mistake it for truth. Treat it as a hypothesis to validate.

3. Map the stages and steps

Define the stages from the customer's perspective, not your internal process. "Sign up for trial" is a customer stage. "Marketing qualified lead entered into CRM" is an internal process.

Within each stage, identify the steps customers take. Be specific. "Evaluate options" is too vague. "Compare pricing plans" and "read customer reviews" are steps you can analyze. Start rough. Your first pass won't be perfect, and you'll refine as you add evidence and bring in more perspectives.

4. Add touchpoints and channels

For each step, identify how customers interact with you. What channels do they use? What touchpoints do they encounter?

Pay attention to channel transitions. A customer who researches on mobile, adds to cart, but switches to desktop to purchase is experiencing friction that may not be obvious. Include touchpoints outside your control as well. Word of mouth, review sites, and social media influence the journey even if they're not yours to manage directly.

5. Layer in emotions and pain points

Add the experiential layer. For each step, capture what customers feel and where they encounter friction.

Plot the emotional arc across the journey. Where are customers confident? Where do they get confused? Where are they delighted? Mark pain points explicitly since these are your improvement opportunities. For each pain point, note why it happens. The cause determines the solution.

6. Identify opportunities

A journey map without opportunities is incomplete. You're not just documenting the experience but identifying where to improve it.

For each significant pain point, define the opportunity. What would better look like? Prioritize based on impact and feasibility. A pain point affecting 5% of customers requiring six months of engineering is different from one affecting 80% that you can fix with a copy change. Document opportunities as actionable items. "Improve checkout" isn't actionable. "Show shipping costs earlier to reduce abandonment" is something a team can work on.

What happens after the map is created

The workshop is the beginning, not the end. What separates useful maps from decorative ones is what happens next.

Assign ownership

Someone needs to keep the map current. This doesn't mean one person does all the work, but someone must champion the map's use and ensure it doesn't decay.

Cross-functional ownership works better than siloed ownership. A map owned solely by the CX team tends to get ignored by product and engineering. Shared ownership across functions keeps the map relevant to how decisions actually get made.

Connect to prioritization

The map must connect to how work gets prioritized. Pain points and opportunities should flow into your roadmap, backlog, or initiative planning.

This sounds obvious, but it's where most maps fail. The map exists in one system while prioritization happens in another. They never meet. Make the map visible in planning conversations. When the team debates what to build next, the journey map should be on the table. When leadership reviews the roadmap, they should see how initiatives connect to customer pain points.

Update regularly

A stale map is worse than no map. It creates false confidence. People reference it without realizing the experience has changed.

Set a review cadence. Quarterly is reasonable for active journeys, more frequent if experience is changing rapidly. Update when triggers occur: new feature launches, process changes, organizational shifts, new research. Don't wait for the scheduled review if something significant changes.

Common mistakes to avoid

Journey mapping has predictable failure modes.

Mapping your process instead of the customer's experience. Your internal workflow and the customer's journey are different things. If your map reads like a process diagram of how your organization works, you've missed the point.

Trying to map everything at once. Multiple personas across multiple journeys creates an overwhelming project that never finishes. Start focused and expand from there.

Building without customer research. Assumption-based maps have their place as starting points, but a map built entirely from internal assumptions reflects what you think customers experience, which is often wrong.

Treating the map as a one-time project. Journey mapping isn't a project with a completion date. It's an ongoing practice. The workshop produces a first draft, and the value comes from maintenance and use.

No clear path from map to action. A map full of pain points with no connection to prioritization is just documentation. If insights don't flow into decisions, the map isn't working.

Getting started

If you're starting your journey mapping practice, keep it simple.

Start with one persona, one journey, one clear use case. Pick something with known pain points or strategic importance. Don't begin with your most complex journey or least understood customer.

Involve cross-functional stakeholders early. Half the value of journey mapping is alignment, so build the map together rather than presenting a finished artifact.

Don't wait for perfect research. You'll never have complete information. Start with what you have, document your assumptions, and validate over time.

The best journey map is the one your team actually uses. Optimize for utility over completeness, clarity over comprehensiveness, ongoing value over workshop output.

FAQ

What's the difference between a journey map and a service blueprint?

A journey map focuses on the customer's experience across stages, touchpoints, and emotions. A service blueprint adds operational depth by showing the backstage processes and systems that support or undermine that experience. Start with a journey map; add blueprint detail when you need to diagnose internal breakdowns.

How often should we update our journey map?

For actively managed journeys, quarterly review works well. Update sooner when significant changes occur: new features, process changes, or fresh customer research. A stale map creates false confidence and leads to decisions based on outdated understanding.

Should we map the current state or future state first?

Start with current state. You need to understand what's actually happening before you can design something better. Future-state maps built without current-state grounding tend to be wishful thinking rather than actionable vision.

How do we get stakeholders to actually use the journey map after the workshop?

Connect the map to how work gets prioritized. If pain points from the map don't flow into roadmap discussions and planning conversations, the map stays decorative. Assign clear ownership and make the map visible in the meetings where decisions happen.

What's the right level of detail for a journey map?

Match detail to purpose. Executive alignment needs high-level stages and key pain points. Service improvement needs granular steps and specific touchpoints. The right level is whatever enables the decisions the map needs to support.